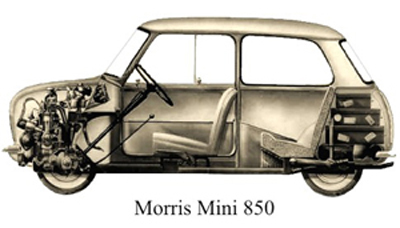

”One thing that I learnt the hard way – well not the hard way, the easy

way – when you’re designing a new car for production, never, never copy

the opposition.”

Category Archives: leading

Colin McRae, RIP

Colin McRae, a racer’s racer. RIP

Power is the greatest…

… way to release your inner jerkdom.

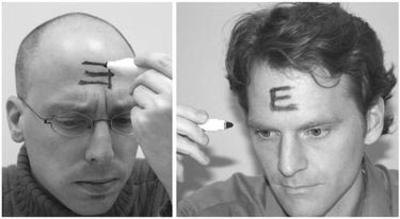

A really chilling study: More Evidence that Getting a Little Power Turns You into a Self-Centered Jerk

A wonderful book about an amazing innovator

The past few weeks I’ve had the pleasure of making my way through a wonderful book about the amazing life and times of Bill Milliken. The title is Equations of Motion: Adventure, Risk and Innovation. An MIT engineer by training, Milliken’s varied and exciting life makes Indiana Jones seem a wimp by comparison, and places Buckaroo Banzai in the category of simpleton. Here’s his bio from the publisher of the book:

William F. Milliken was born in Old Town, Maine in 1911. He

graduated MIT in 1934. During World War II he was Chief Flight Test

Engineer at Boeing Aircraft. From 1944, he was managing director at

Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory (CAL/Calspan), retiring as the head of

the Transportation Research Division, which he founded.Bill joined the SCCA in 1946 (Competition License No. 6) and

contested over 100 races as well as holding many responsible club

positions. Milliken Research Associates was founded in 1976 and

continues as a foundational research asset to the automotive and auto

racing industries. Bill remains active in MRA, which is now run by his

son, Douglas L. Milliken.Bill is co-author of Race Car Vehicle Dynamics and Chassis Design.

He is an SAE Fellow, member of the SCCA Hall of Fame, recipient of the

SAE Edward N. Cole Award, the Laura Taber Barbour Air Safety Award and

many other citations for innovation.Today Bill lives in the Buffalo, New York area with his wife,

Barbara. He continues to consult with racing and chassis engineers. He

jogs around the half-mile track behind his home and spends several

evenings at the gym.

This book works on many levels. It’s a fascinating look at the world of aviation pre- and post-WW II. You get a ringside seat at the dawn of the sports car movement in the United States. It is an honest glimpse at what life was like in America around the turn of the Twentieth Century, and what it feels like to enter early adulthood under the weight of a major economic depression. Most of all, it’s a tribute to what it means to be a racer, to be an entrepreneur and a generative person, to get up each morning and say "How am I going to change the world today?".

I believe "design" is a verb and "innovation" is best thought of as the outcome of relatively tight set of behaviors and life attitudes embodied to their fullest by people like Bill Milliken. He designed his life, and continues to live a remarkable one today.

I love this book.

PS: if you don’t have the time (or inclination) to read Equations of Motion, please take a look at this charming profile of Milliken written by Karl Ludvigsen: Mister Supernatural

Imagining innovative behavior, vividly

I don’t believe creativity is about thinking outside of the box. I think it’s about making connections across otherwise unconnected boxes; it’s about pattern recognition.

So, if you will, please indulge me as I communicate a creative link I just made across the writing of two of my colleagues/friends/fellow bloggers, Bob Sutton and John Maeda. Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about what happens when human nature meets the need for organizations to be scalable and sustainable, and I think Professors Sutton and Maeda have — quite independently — hit upon a key point. First, Maeda:

When I was younger, I often tended to think the worst of others when

I felt sleighted in some seemingly unfortunate way. "I have been

wronged because other person X has intentionally wronged me with motive Y." I punish the other person by publicly expressing person X’s (alleged and) imagined motive Y.Often you discover that your imagination has done its work the way it

should — it imagined something happened in elegant detail without ever

actually happening. The net result is not only embarrassment, but even

worse your own poor intentions or habits with respect to others are

revealed. You imagine most vividly what you do yourself.The best route is to avoid situations of thinking ill of others by

enacting exemplar behaviors yourself. You are likely to be in a better

position as you are in a better mood and more resilient to adopting

negative behavior — thus affecting your surrounds with the positive

energy necessary to do amazing things in this world.

And then Sutton, as expressed in two points from his "15 Things I Believe" manifesto:

I believe quite strongly that people are more likely to engage in innovative behavior when they are in a flow-like state of happiness. It’s hard to be innovative when you are unhappy yourself, because as Maeda says, "You imagine most vividly what you do yourself." And it’s hard to engage in innovative, value-creating behavior when you’re only looking out for Number One — all the innovative cultures I’ve had the pleasure to work in were notable for their relative lack of narcissistic behavior. If, as Sutton says, "… unvarnished self-interest is a learned social norm…", then innovative behavior should be one, too. People aren’t innovative or not, but their behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes are.

Thank you for the connection, John and Bob.

metacool Thought of the Day

"If you’re not prepared to be wrong, you will never come up with anything original."

– Sir Ken Robinson

A school for learning

I’m fascinated by Fuji Kindergarten, as profiled by Fiona Wilson in Monocle magazine. Fuji Kindergarten is a school whose building was designed by Tezuka Architects.

I wish my kids could go to Fuji Kindergarten. I wish I could have gone to Fuji Kindergarten. I wish I could go now. Fuji Kindergarten, I reckon, is what happens when "chutes and ladders" meets a thought experiment about education which goes back to first principles. What makes it so unusual an educational institution is that it places the most emphasis on learning, rather than on teaching. And on students rather than teachers (and, I’d wager, on teachers rather than administrative staff…). Think about that one for a while.

Next time I travel to Japan, I’m going to try and visit Fuji Kindergarten. In the mean time, I’m going to try and apply some of its lessons to our own school project over here at Stanford, called the d.school. Perhaps we can work harder to make the architecture really support the learning process behind design thinking.

By the way, I’m beginning to really dig Monocle magazine.

The Name of the Game is Work

The big thing about playing video games used to be that they were the new golf, a novel way to hang with friends and business associates in order to maybe bond, collude, or even get some productive work done. But it’s not just about golf anymore: Aili McConnon from BusinessWeek just published an article about the intersection of work and gaming, and I’m here to tell you that video gaming is about work. I even landed a quote in there referencing the lessons to be had from playing MMOG’s:

The lessons learned in these games become increasingly useful as

companies become less command-and-control and more a series of

distributed networks around the world. The future of work

is here; it’s just disguised as a game.

The article also talks through some interesting game-related stories from McKinsey, J&J, and Philips, and also has a great insight from my Stanford d.school partner in crime Bob Sutton.

I really do think that you can learn a lot about where this whole Web 2.0 thing is going by playing games online. Learning by doing, serious play, and all that.

Director’s Commentary: Cradle to Cradle

Here’s a great Director’s Commentary: architect, designer, and author Bill McDonough speaks about cradle to cradle design. If you’ve never heard him speak, I highly encourage you to give a listen. And if you have, well, I learn something new each time I listen.

I first heard Bill speak on February 11, 2003 at a lecture given at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business. I remember being in that miserable state of having just recovered from a winter flu, and not really wanting to do anything more than go to sleep, but something told me to leave work early to grab a good seat.

I’m glad I did. His words changed my life, because for the first time I saw a potential path forward. I took a class on environmental science in the Fall of 1988 as a freshman at Stanford, and had been aware of the science of global warming and of the importance of toxic concentrations of chemicals since that time. But, as a design engineer, I never felt there was much I could do beyond specifying good materials and making sure they were labeled for recycling. McDonough’s Cradle to Cradle philosophy changed all of that for me, because it helped me see clearly the value of being able to combine, at a personal, corporate, societal, and global level, the lenses of business, human values, and technology.

On being remarkable

Seth Godin has a provocative post about what it takes to be remarkable: Is good enough enough?

Here’s my favorite part, on what being remarkable entails at a personal level:

First, it would require significant risk-taking. Which would include

the risk of failure and the risk of getting fired (omg!). Can you and

your team handle that? If not, might as well admit it and settle for

good enough. But if you’re settling, don’t sit around wishing for

results beyond what you’ve been getting.Second, it would mean that every single time you set out to be

remarkable, you’d have to raise the bar and start over. It’s exhausting.Third, it means that the boss and the boss’s boss are unlikely to give you much cover. Are you okay with that?

Are you willing to engage in innovative behavior? A lot of the time it hurts.