This factory tour is incredibly interesting, for three reasons.

First, the Porsche 911 reimagined by Singer Vehicle Design. It’s beautiful and seductive and I just want to jump in one and back it into corners. It’s an exemplary instance of the right group of people doing something absolutely to the hilt and beyond. Singer’s mantra “Everything is Important” shines through on every detail of the car and its production process. It’s so rare to come across an object designed and produced without regard to cost, and it’s instructive to observe how that mindset shapes the finished product and the way the market receives it. (Spoiler: as revealed toward the end of the video, they don’t have to engage in any traditional go-to-market activities in order to sell these Porsches; demand is so high that they’re going to cap production lest Singer inadvertently jump the shark.)

Roman Mars exhorts us to Always Read the Plaque; in much the same way here at metacool HQ we endeavor to Always Take the Factory Tour. Always. In this case, Singer’s factory is a fascinating mix of industrial recycling (upcycling) center, Saville Row backroom, and aerospace carbon fiber fabrication skunkworks. So perhaps the second notable thing about this video is what it can teach us about organizational culture. Now, culture is about what you do and how people behave as opposed to what you say you do and how you hope people behave. And there’s no place in an organization more oriented toward the doing of things than a manufacturing line. It’s literally where the things that customers pay for are produced. From that standpoint, what we witness on the tour reveals so much of what makes Singer tick. This is no slick tour of Singer produced by a PR agency — it’s just CEO Mazen Fawaz taking us on an unscripted stroll around the building. A telling moment in the tour happens at the 1:35 mark where Mazen informs us that each incoming “donor” Porsche 964 gets dismantled offsite because doing so under this roof would be too messy. Not an obvious choice to make from a business perspective: more complex, likely more expensive. But, with that operating decision in mind, look at the gleaming white floors of the Singer factory as evidence that what the CEO says, what actually happens in the factory (or doesn’t, in the case of incoming car processing), and the stated company mantra are all in alignment. Everything is in fact important at Singer, and is executed upon as such.

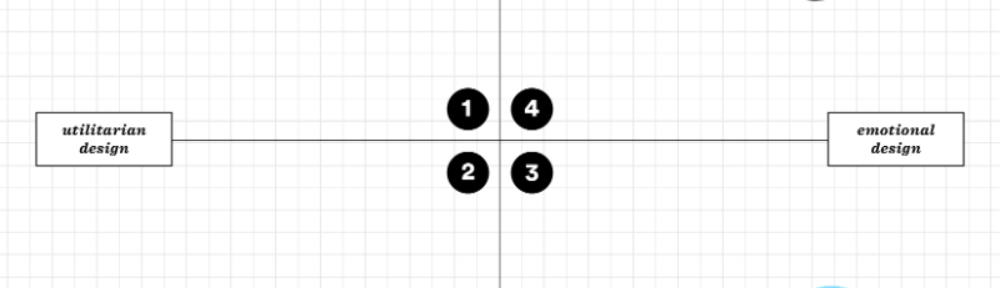

Third, Quadrant Four and the future of objects whose value is rooted in the fact that they are singularly designed to evoke certain types of strong emotions. Eight years ago, at the behest of Reilly Brennan’s Future of Transportation forum, we discussed the forking of the 20th century conception of the automobile. Simply put, four radically different types of vehicles result from this fork in the road, the most interesting of which is called Quadrant Four. Per that 2015 essay:

Internal Combustion-powered cars as the new Patek Philippe watch—more complex and less capable than their solid-state cousins, but a visceral thrill as well as a status symbol for those who choose to display their money this way. The recent run-up in prices of vintage Porsches is evidence that non-autonomous cars with manual transmissions and gas motors are already being priced in anticipation of this scenario—the thrill of driving a complex machine fast will become a rarefied luxury experience. Here cars really will be like horses, a pastime of enthusiasts, with dedicated spaces for frolicking.

Singer, the vehicles it creates, and all of its commercial success represent an existence proof for the idea of Quadrant Four. On paper, a reimagined Porsche 911 rolling out of the Singer factory is not quantifiably a better automobile than the brand new 992 you might spy on your local dealer’s lot. The newer 911 is faster, more economical, cleaner, safer. But for many people, a Singer is an infinitely more interesting (and therefore valuable) car — a car being the antithesis of a computerized, close-to-perfection auto-mobile. As Porsche from Singer is something you want to fall in love with, much as you would a horse, a mechanical watch, an old house, or any other analog object.

Isn’t that the point of creating great stuff? Making things that people can love?