Rob Glaser’s approach to restructuring the Professional Bowler’s Association (PBA) is proof positive that you can prototype anything, and that we should design ventures to have the let’s-learn-as-we-go flexibility of a good prototype. In this Wired article, Glaser’s business partner Chris Peters describes how they restructured the league to take advantage of the iterative product development process they knew so well from working in the software industry:

"You launch version 1, put it out there, see what you did wrong, and you come out with version 2. It’s a process I understood well. You don’t spend 10 years on a grand plan and then finally put something out there; that’s just stupid. You’ve got to have a constant product cycle."

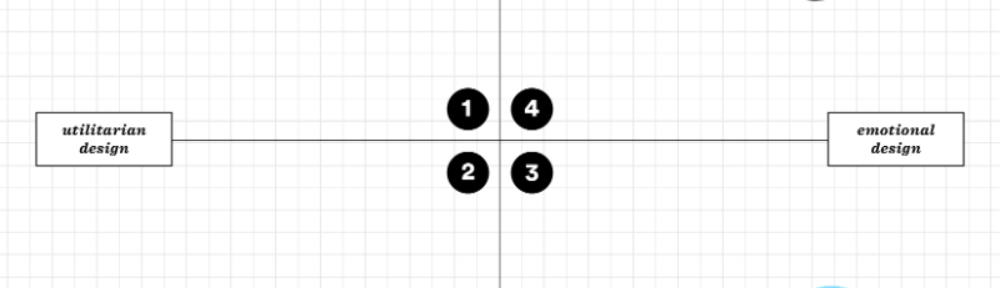

Among the lessons learned by getting out there and doing something: emotion rules, and there are players willing to take on the challenge of adding NASCAR-type theatrics to formerly staid bowling lanes. There’s no way a group of smart people talking to a whiteboard could have come up with that nugget.

If you set up your venture as a prototype, you can focus your energy on discovering a golden framework so that the right implementation recipe emerges organically.