"I have said that knowledge is the purpose to act, and that practice implies carrying out knowledge. Knowledge is the beginning of practice; doing is the completion of knowing."

Category Archives: innovating

Location Change: d.school Conference Now at Hewlett 201 on the Stanford Campus

ALERT! ALERT!

We have had a BUNCH of folks sign-up for our conference on Creating

Infectious Action so we are moving to a bigger room. It is now in Hewlett 201.

Here

is the link to

the new location. The event still goes from

3:30 to 6 with a reception to follow. See you there!

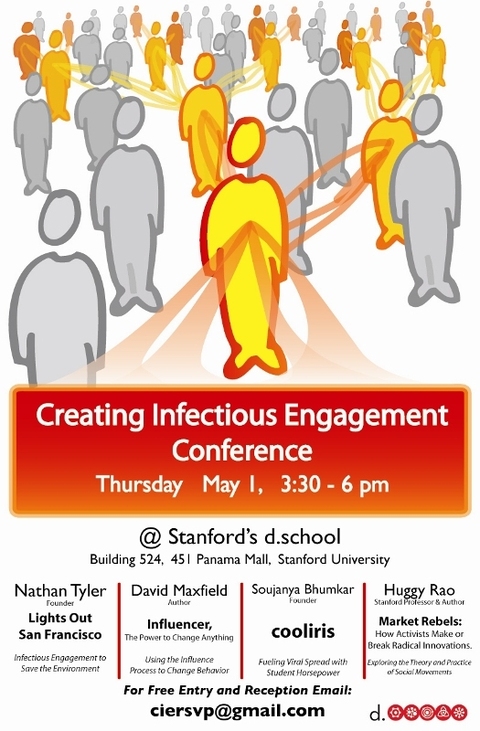

May 1st Innovation Conference @ Stanford d.school

The Stanford d.school class I’m co-teaching on Creating Infectious Engagement is holding a conference next Thursday May 1st from 3:30 pm to 6:00 pm. Will you please come if you are in the area?

We’ve held a conference the previous two years of teaching the class, and each one has been a highlight of the quarter. Previous speakers have included luminaries such as Steve Jurvetson, Perry Klebahn, Dennis Whittle, Mari Kuraishi, and Jessica Flannery. Folks that knock your hat in the creek.

This year is no exception. I can’t wait to hear all of them speak, and Ruggy Rao in particular is one of my favorites. Please RSVP to Joe Mellin at ciersvp@gmail.com if you will be joining us so that we can arrange for the right quantity of tasty vittles and libations.

Where? Our KILLER new d.school space at Stanford Building 524. This building is right across from Old Union, near the Design Loft.

Since this is all about creating infectious action, please tell your friends all about it!

The ultimate long tail business model?

Here’s the most radical version of a long-tail business model yet:

Here’s the video summary:

metacool Thought of the Day

"When I am no longer controversial I will no longer be important.’

– Gustave Courbet

Are people upset with you? It is because what you’ve done is so bad it is shameful, or because it is so polarizing, so rooted in a strong point of view that all but the most progressive or forward-thinking people don’t understand and "get it"? Do you want to design for the mass market of today or tomorrow? Are you designing under the old paradigm or for a new one?

Having a strong point of view, informed by real human needs, is at the core of how design thinkerdoers behave. They make choices, and thus end up with strategies grounded in the needs of real human beings, real organisms, and the planet, and end up with something whose value proposition is intelligible, which creates real value for a real soul somewhere in the world, and is designed to spread and reach the right people, whether that be a bushel or a billion.

Making choices, taking the route which may be controversial or even painful, is about being willing to live with innovative outcomes.

Want an innovative culture? Status differences blow

When it comes to bringing cool stuff in to the world, I’m a big fan of Honda. If you’ve been around metacool for any period of time, then you know that I admire Honda a great deal. I’ve written about Honda’s ability to innovate on a routine basis, about the fact that it is led by someone who really — really! — knows the business, about its ability to advertise truth rather than myth, about the pickup they make which I dearly want and am only waiting for the diesel model to arrive to purchase, and about kick-ass minivan race cars made by Honda’s own employees on their own time because, well, kick-ass minivans are a kick in the ass if you’re a racer. Just about everyone at Honda, it would seem, is a racer, as explained in this great article in Fortune:

Unlike Toyota (TM),

which is stodgy and bureaucratic, Honda’s culture is more

entrepreneurial, even quirky. Employees are paid less than at the

competition, and advancement is limited, given Honda’s flat

organization. Their satisfaction and fierce loyalty to the company come

from being around people like themselves – tinkerers who are obsessed

with making things work.

At the risk of making a broad generalization, I would say that innovative startups and more mature organizations capable of innovating on a routine basis (like Honda) share two key elements in common: first, a remarkable lack of status differences among employees, and second, a low-friction environment when it comes to the meritocracy of ideas. I actually believe the latter is a function of the former. Why?

We all have 24 hours a day to live our lives. We have finite time and energy at our disposal. If we all start with the same account balance, some of us choose to spend it worrying about what our boss’s boss thinks about us, or on over-preparing for that internal review meeting, or on wondering what our growth path is. Others say "this is this" and get on with being generative, pushing ideas as far as they can go, and helping others see what works by gathering real evidence from the world and letting opinions fall by the wayside. Status differences are energy sinks. Do you want to spend your life worrying or producing? Dramatic status differences lead to dramatic wastes of energy.

Show me a group of people who worry less about where others think they stand, and more about how things are really going and how they might do things better and cooler, and mark my word, that’s the group of innovators.

A wonderful example of a disruptive business model

Here’s a great example of a low-end disruptive business model: Psychotherapy for All

The more I work on the creation of disruptive business models, the more I’m convinced that there’s almost always room for a disruptive model. One just needs to start with human needs and look hard, work hard for it. The design process needs constraints. A lack of viable solution spaces is more a reflection of poor innovation process than a statement of fact; it is a lack of generative contraints which leads to dead ends.

I can think of no better design constraint for the genesis of disruptive business models than trying to serve the needs of people living on a few dollars a day. What, for example, might happen to pace of innovation in our US healthcare system if we were to take notes on disruptions such as this one, or from the Aravind Eye Care System?

Director’s Commentary: Amia Chair

Here’s a marvellous Director’s Commentary about the Amia chair. Thomas Overthun, a colleague of mine from IDEO, and Bruce Smith of Steelcase take us through its genesis.

Watch the video, and find out why an integral part of innovating is being willing to cut everything in half. It’s all about strategy that makes your hands bleed: I challenge you to find something in your work life that you should cut in half on the bandsaw, if only metaphorically.

Why not?

Rethinking management education, organizing for routine innovation, Charles Eames, and the importance of holding the air gun trigger down

Just the other week I had the pleasure of dropping in on one of Bob Sutton’s graduate courses at Stanford. I was supposed to be on paternity leave, but if you haven’t noticed yet, I have this thing for racing and cars, and well, it’s only a ten-minute walk to the Stanford campus from where I live, and my wife is a kind and charitable soul when it comes to indulging my passion for gearhead gnarlyness. Call it a busman’s holiday. This particular class (pictured above) deals with navigating innovations through complex organizations. Yes, that’s a real NASCAR racer. Yes, those are real live Stanford graduate students. And yes, that’s what February in California looks like.

So what’s going on in the photo? A very interesting exercise in teamwork which exposes and illuminates all sorts of juicy issues in organizing for innovation. In this class, Sutton, co-teacher Michael Dearing, and guest lecturer Andy Papathanassiou of Hendrick Motorsports get teams of students to go through the process of changing the tires on a NASCAR machine. It is harder than it looks: the tires and rims are heavy, the car wants to fall of the jack (well, it is on jack stands, but it feels like it wants to fall off), and the lug nuts seem to be cross-bred with jumping beans. You can read more about the class exercise here and here.

After 60 minutes of watching teams of students go from zero to hero in terms of their tire-changing acumen, my head was buzzing with lessons for those studying the art and science of bringing cool things to life:

- Mind your modalities: How do you want to grow? What are you trying to accomplish? At first glance, changing a tire is easy, right? Take it off, grab a new one, bolt it on. But how might one reduce the cycle time by 10%? 50%? 90%? How would you organize teams to reach those goals? And on the other hand, how do you create teams that are able to change tires in a hurry in the heat of the Daytona 500 without missing a beat? And how do you get one team or organization to be good at both innovating and executing? I think it is all about minding your modalities, knowing what you are shooting for at any instant. If we want to commit to taking 20% off of our tire changing times over the course of a racing season, perhaps we need to start an R&D department whose function is to create extreme variance, to find those weird solutions that will lead to paradigm shifts. And perhaps we need to establish a test team whose job it is to sort through the revolutionary stuff coming out of R&D in the name of focusing and honing a few promising solutions. And then we need to find a way to train our front-line team so rigorously that they can execute flawlessly on that killer idea birthed in R&D, and matured by the test team. Minding modalities is about recognizing when it’s about business by design versus business as usual, and structuring and leading things accordingly. It’s about embracing variance when it is needed, and driving it out when it is not. The best racing teams, such as Hendrick, Penske, and Ferrari, know how to do both. They are masters of innovation modalities.

- Seek out constraints: when staring in to the abyss of a blank sheet of paper, constraints provide a vital toehold, a way forward. Not necessarily the way forward, because rarely is innovating a linear process, but a way forward nonetheless. NASCAR is an incredibly constrained environment when it comes to the design and operation of race cars. Everything is templatized and mandated to the nth degree by a central organization. And yet, creativity flourishes, the leading edge continually moves forward, and the garden blooms. Sure, there are some a few "cheating" weeds here and there, but that’s racers being racers. Cheating is just a way of signaling that that a constraint is likely invalid. Constraints = Progress. Infinite possibilities lead to stasis.

- Organize for information flow: How do you design an organization so that it can innovate where it needs to innovate and execute when it needs to execute? Here’s a clue: drawing org charts won’t get you there. Ideally, one thinks first about critical information flows which need to occur in order for certain outcomes to be realized. Once those information flows are identified, the organizational structure emerges fairly organically, with an org chart as a by-product. I was thrilled to meet Andy Papa at this class exercise, because Hendrick does a wicked job of organizing for creative information flow. As a pioneer of the multi-car team in NASCAR, Hendrick has cracked the code on how to structure an organization such that variance-reducing, execution-minded focus (separate teams each competing to win the NASCAR cup) can coexist with a non-zero, variance-embracing, innovation-seeking worldview (everyone in the organization sharing information in order to identify patterns which lead to revolutionary and evolutionary innovations, and hopefully, victory for all). Racing teams have no choice but to evolve or die, and to make tough choices or cease to be relevant, so I often look to them for inspiration when faced with organization design challenges in my own work. You read it here first: Hendrick is the New Apple. Or the new GE.

- Learn by Doing: I’m entering broken-record mode here, but the teams that did the best in this class challenge were those that dove in and started changing tires. Instead of arguing over who would be the CEO of rickybobbytirechangers.com, and who would be leading the war for talent, these teams got down on the ground and got their hands dirty. By the wail of the air gun, thee too shall witness one’s strategy emerge. And so it happened — the best way around a NASCAR wheelwell can’t be thought through in one’s head, but has to be iteratively solved with hand and heart and brain. In other words, strategy that makes your hands bleed.

Note to self: if ever I find myself swapping out new rubber in a big hurry, keep the trigger down on the air gun. WFO, baby!