I’m more than a little obsessed with OK Go’s new video, I Won’t Let You Down. I love the tune, the choreography is impressive, and I can’t get over the chutzpah it takes to film a single-take video using an octocopter drone:

But what’s kept me coming back to watch it over and over are the lessons we can take from OK Go and their seemingly limitless appetite for innovating. Here are my top three:

1. Innovating happens when you embrace serendipity

You can’t think your way to an innovative outcome. Breakthroughs come from giving yourself the time to fool around with a bunch of random elements. By getting out of the office and doing stuff, you learn where to find the awesomeness you seek.

Here is how OK Go’s Damian Kulash describes the process of serendipity that fed this video:

What we try to do is get the best idea we can at that desk and then get out into the place where we’re going to be making whatever we’re going to be making and play with it a lot. We have a lot of trial and error, a lot of figuring out what does and doesn’t work. Usually, by the time we’re done with that process, the idea is pretty dramatically different from what we started with… And it means that we waste a lot of money and our production value is… we don’t shoot the world’s most clean and beautiful stuff, but we have videos that no one else could have.

This isn’t about waiting for inspiration from a muse, it’s about intentional serendipity, making your own luck via the hard work of experimentation and iteration. OK Go’s videos are so memorable because of the countless iterations they go through to get to the finished product. Because they’re careful to set the stage for serendipity to flourish, each cycle of experimentation increases the odds of them bumping into a piece of magic.

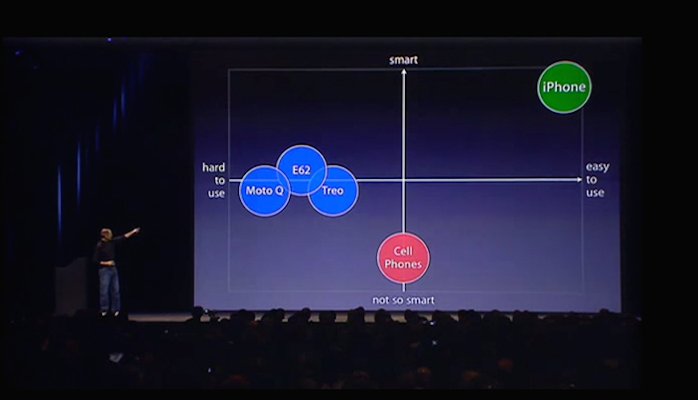

2. Business model innovations ripple through everything else

OK Go’s business model innovation was to choose a different metric: instead of tracking the number of albums sold—the usual measurement of success in the music industry—they focus instead on the passion of their followers.

OK Go made a decision early on to bypass radio and MTV and go directly to YouTube with its unique style of low-budget, single-take music videos. The resulting channel conflict (“You’re letting people listen for free? What about our sales?”) flew in the face of conventional wisdom about how to stay in business as a rock musician.

This unexpected choice is key to understanding the band’s ensuing success: when your goal is making your fans happy, you focus on the music and the videos and the quality of your tours, thereby setting up a virtuous cycle. Each time they create a video like I Won’t Let You Down, they affirm their relationship with existing fans, and win new ones. When it comes time to create their next video, their priorities will be in order, and mustering the courage and resources to do something even more spectacular will be relatively straightforward.

On the other hand, focusing on album sales means listening to a lot of people who may or may not care about the art—the marketing guys or the huge distributors. And that distracts you from doing the one thing you need to do as a rocker: create great, unique music. So here’s a question to ask yourself: is your business model helping you actually win at the thing you’re in business to do?

As it happens, those Honda UNI-CUBs piloted by OK Go are also the result of a business model innovation. In 1960 Takeo Fujisawa (an organizational design genius, and Soichiro Honda’s business partner) created Honda R&D as an entity independent of—but funded by—its parent Honda Motor Company. This structure was all about embracing serendipity. It gave Honda’s R&D scientists and engineers the permission to tinker and generally fool around with technologies that had no obvious short-term relationship to cars or even Honda itself. Over the years, Honda R&D has created many innovations that have eventually become mainstream hits.

3. Vision + Guts + Perseverance = Innovative Outcomes

The magic of many of OK Go’s videos is that they’re hugely creative performances done in just one massive, risky, glorious take. They couple a big vision with big guts. It’s the film equivalent of tightrope walking—one errant UNI-CUB and it’s back to frame one.

Pulling it off in grand style requires a ton of perseverance. The risks involved could lead to a diminished vision (“Why don’t we make this easier on ourselves?”) and a less vibrant performance (“I keep screwing up the choreography—I’ll dial back my grooviness”). But OK Go always has the guts to dream big, and the dogged perseverance to pull it off.

This specific video required around 2,300 people collaborating on about 60 practice runs and 44 filmed takes, 11 of which were done to completion. Of those, only three were of acceptable quality. Just imagine the emotional and logistical fortitude it takes to restart the filming process after a minor flub.

It’s the same with Honda. UNI-CUB isn’t even on the market yet, but Honda gave OK Go a second-generation iteration to use for this video. UNI-CUB literally stands on years of patient research that went into the company’s humanoid robot ASIMO and untold other projects that would seem to be unrelated on first glace.

It took 68 years to get here; back in 1946 Soichiro Honda wouldn’t have been able to imagine that his creation of Honda R&D would eventually lead to four men in black suits riding his company’s vehicles around on something called the “internet,” while thousands of women with bright umbrellas danced in psychedelic patterns. But that’s the nature of innovation—you don’t always know what the flower garden will look like, but that doesn’t stop you from planting the seeds.

So dream big, let it all get messy, and put in the hard work to make it happen.

And keep those umbrellas twirling.