I really enjoy listening to the director’s commentary track on a movie DVD. How else could I confirm my suspicion that the closing credits of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou are an homage to the way the credits were presented in Buckaroo Banzai? What excites me about the director’s commentary is the idea of future filmakers learning their craft not just at film school or via personal experimentation, but with the digital equivalent of an oral storytelling tradition.

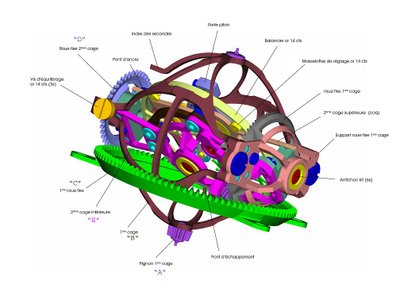

Wouldn’t it be great if, in a similar fashion, we could hear and see great designers talking about their craft? When I was a practicing engineer designing tangible things, there were tens, even hundreds of details embedded in my designs which I knew about, maybe the rest of my team knew about, but which were essentially invisible to the world at large. Which is fine; it isn’t the job of end users to be thinking about the kinds of details and decisions that interest a professional design thinker. But for students in training, and for other professionals, what better way to truly appreciate the enormity of the task of design than to take a walkthrough around a real design with another real, living designer?

Before we move on, let me explain my irrational — perhaps even unhealthy — interest in the Honda Ridgeline. Unique among pickups in that it was designed using a human-centric design process, the Ridgeline is an incredible piece of design and engineering. Sure, the aesthetics are a bit jolie-laide, but they’re the result of Honda designers thinking and acting much like designers from the Citroen of old, always pushing limits technical and aesthetic — to the limit. For 90% of pickup buyers, this design just works better. It’s really, really cool, and that coolness is the sum total of thousands of clever, human-centric design decisions, most of them invisible.

How do I know? Thanks to a director’s commentary. Here are some "director’s commentary" videos with Gary Flint, the leader of the Ridgeline design team, walking us around the final offering. Even if you don’t find cars exciting, take a listen to the first, upper left video — you’ll be amazed by the attention to detail and deep thinking that went into the design of the cargo area. Amazing.

photo via Flickr