“If failure can be explained, and it’s not based on lack of morality, then to me failure is acceptable, and you have learned from it and you can start again.”

From the Department of Don’t Get Ready, Get Started

When it comes to making a difference in the world, I am ever a disciple of Perry Klebahn, and try to live by his mantra of “Don’t Get Ready, Get Started”. Better than any other, that phrase captures the essence of my philosophy of innovating.

I also take great inspiration from Harvard Business School Professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter. Her writings and books provide great insight into the art and science of bringing cool things to life, and I find all of her teaching quite inspiring. My favorite is her essay Four Reasons Any Action is Better than None.

In my aspirational vision of a perfect world, Perry has this essay framed and hanging on the wall of his office at Stanford. Please give it a read. But for the sake of reminding me to keep going back to it, here are her four big points on why getting started beats getting ready:

- Small wins matter

- Accomplishments come in pieces

- Perfection is unattainable anyway

- Actions produce energy and momentum

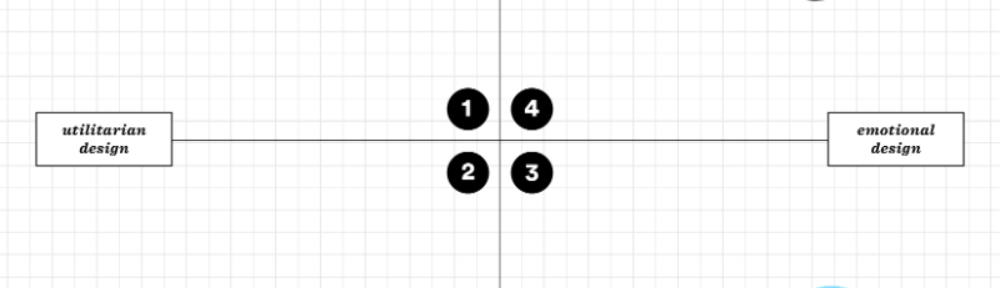

Energy. Confidence. Momentum. These aren’t words you run across in most of the literature about innovation, whose authors are obsessed with creating the best (or most esoteric?) 2×2 innovation typology matrix. Or even a three-dimensional one. I am guilty as charged on that front. But for anyone who has engaged in the challenging endeavor of bringing something new into the world, you know that it’s much more about confidence and momentum than it is about where you sit on someone’s theoretical design thinking/strategic thinking/innovation thinking spectrum.

Okay that’s it for today. Stop reading this and get back to work! Get started and… GO!

Ruminating on design principles for new ventures

Having spent the past 18 months of my life launching five new ventures here at IDEO, I’ve been thinking a lot about the design of new ventures. Meta design thoughts, if you will.

I don’t have any big revelations to share with you yet, as this post is the beginning of the process of pulling all of that together, but what I’m trying to pull together is a personal take on how to create new ventures on a routine basis. I have this for how to design and lead a creative culture at scale, I have a personal take on how to lead teams, and I have my own take on hardware and software product development. I’ve had a working model of new venture design for the past eight years, but it was largely tacit, so I’m going to take some time over the next few months to hammer it out as one would a sword of the finest Valyrian steel.

I suspect this will lead to a rethink of my Principles for Innovating listed down the side of this blog, which would be cool, as I haven’t rethought those in a few years, and during that time I’ve definitely rolled up more than a few new miles on the life experience odometer.

I just discovered Andy Weissman. How has the universe been hiding this guy from me? Or more apt, what rock have I been hiding under? No matter, on the point of making decisions about and in a new venture, I really like his post titled The Chaos Theory of Startups. Here’s my favorite passage:

Your framework for making decisions matters as much or more than the decisions themselves, because the “chaos” of the system makes most outcomes indeterminate (again, chaos theory: “long-term prediction [is] impossible in general”).

So you need a framework, a set of first principles. That then guide your decision making and problem solving.

Taken a step further, I’ve always thought the most useful thing a venture investor can then do for a company is simply help them come up with that framework, that scaffolding, to throw all those choices into. And not specifically to help make the choices themselves. After all, one of the primary ways venture investors can add value is through having seen dozens and dozens of these chaoses. Presumably, we are well-suited to help determine frameworks for decision making in future, similar chaotic scenarios.

I think there are lots of different frameworks or first principles for decision making; it’s not a limited set. This may mean that figuring out the framework may be the hardest question of all.

Scaffolding: that’s the metaphor I need to move this thinking forward. What’s a set of component parts (first principles), that I can assemble so that they can be used to construct decision-making frameworks to fit any situation? I don’t aspire to create a perfect framework at all—what I want is a bunch of stress-tested, bullshit-detected, thoroughly vetted building blocks that can be tailored to any design situation you may find yourself in.

I’ll be writing about this a lot over the next few months. Would love any thoughts, ideas, and inputs you may have. By all means, please drop me an email or leave a comment or send me a tweet.

Laughing: the killer app for teams?

Before you attend the TED conference, the organizers ask you to jot down three “Ask me about…” sentence completion phrases (kind of like tweets, but even fewer characters). These end up as a footer on your name badge. Cocktail party conversation starter. For TED 2015, one of my three was “Laughing”.

As someone who spends all of their professional time counseling and guiding creative teams, as well as helping to set up the conditions for them to thrive (in my humble opinion, organizational architecture is destiny, but that’s a blog post for another time), I’m fascinated by the role of laughter and humor in the life of a thriving team. While I don’t believe that every second of each day should be full of mirth, laughter, and frolicking leprechauns, my experience says that groups of people with a healthy team dynamic are able to share a laugh when appropriate. And at an interpersonal level, sometimes the best recipe for diffusing a difficult moment is the simple mix of an easy smile and a good laugh.

So imagine my delight at being able to listen to Professor Sophie Scott give her fascinating talk on why we laugh. She really knocked my hat in the creek. Here’s my favorite part of her talk:

The fact that the laughter works, it gets him from a painful, embarrassing, difficult situation, into a funny situation, into what we’re actually enjoying there, and I think that’s a really interesting use, and it’s actually happening all the time.

For example, I can remember something like this happening at my father’s funeral. We weren’t jumping around on the ice in our underpants. We’re not Canadian. These events are always difficult, I had a relative who was being a bit difficult, my mum was not in a good place, and I can remember finding myself just before the whole thing started telling this story about something that happened in a 1970s sitcom, and I just thought at the time, I don’t know why I’m doing this, and what I realized I was doing was I was coming up with something from somewhere I could use to make her laugh together with me. It was a very basic reaction to find some reason we can do this. We can laugh together. We’re going to get through this. We’re going to be okay.

That’s it: if we can laugh together, we can get through almost anything, and it’ll be okay.

By the way, please give Sophie a follow on Twitter. She’s a hoot!

Design Inspiration: Donald Brink

Some of the best innovation advice I’ve ever heard

We had an embarrassment of riches. It was 1998, and I was leading an IDEO design team that had dreamt up so many cool ideas — and had created a range of working prototypes now standing in front of us — that we couldn’t decide which direction to take. Somewhere, shimmering out in the distance, was never-seen-before perfection, but we just didn’t know which path to take to get there.

In short, we were doing great work. But we were also stuck.

Then, as we stood pondering the prototypes that we’d made, and debating which was the most awesome, IDEO founder David Kelley strolled by to say hello and to watch us demonstrate our ideas. He listened patiently as we explained our dilemma, and responded with one simple question: “What’s the best alternative available to people today? Choose compared to that.”

Behind David’s powerful question is the best innovation advice I’ve ever received:

Compare to reality, not to some imaginary standard of perfection.

The truth was that even our least amazing prototype was miles ahead of the competition. It also happened to be the simplest concept, and the one that most tightly addressed the actual needs we’d heard from people we had interviewed and observed. Even if it didn’t fulfill our fantasies of perfection, we chose that option as the way forward, and we ended up nailing it: our award-winning design sold like hotcakes. Fifteen years later, it’s still in production, making people happy.

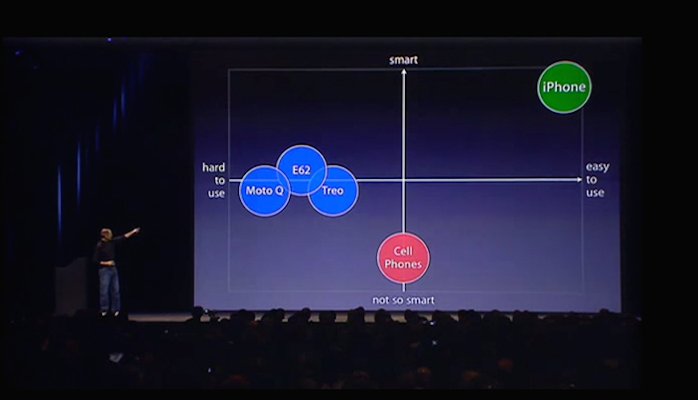

I put David’s advice to work every week, because when you get a bunch of talented, energetic people together, it’s incredibly tempting to try and cram as many amazing ideas as you can into whatever it is you’re creating. That impulse leads to things like the Amazon Fire Phone, a technological tour de force that included everything but the kitchen sink, but ultimately failed to satisfy. Compare the Fire’s laundry list of features to the reality-based point of view communicated by Steve Jobs at the 2007 launch of the iPhone, shown above.

Always going back to a benchmark anchored in reality forces you to articulate a clear point of view about what’s truly important. This is the path to excellence.

Some say that rooting your choices in reality is a sure path to mediocrity, but nothing could be further from the truth. Dedicating yourself to understanding what people really want — how they’ll experience a product in the real world — forces you to get away from your desk and make a tangible difference. Instead of just talking about a grand paradise of what might be, putting in the effort to understand people’s day-to-day lives, and then actually producing something that works, is what separates a true innovation from a merely good idea.

Great innovators dream, but they are also relentless about comparing those dreams to the real world, and acting accordingly.

image credit: Ernest Kim

Design Inspiration: Jay’s Citroen DS

metacool Thought of the Day

“Like cement, the cultural foundation for new projects and companies sets early. Those who focus on raising outside capital and achieving fundable milestones have a very difficult time getting off that VC treadmill. Those who focus on creating value for customers and generating positive cash flow from the very beginning are able to make their own decisions independent of competing outside interests.”

photo credit: Christopher Michel

WTF is a Product Manager?

Product management is a critical part of a healthy product development process, but it can be difficult to pin it down the specifics of it as a role.

I really like this essay by Ernest Kim, WTF is a Product Manager? Definitely worth a read—he has a lot of miles under his belt as a product developer, so this is reality speaking.

Here’s a choice bit:

An example I’ve used in the past is that the designers and developers at Nike are so good that they could create a shoe that looks like a boat, yet still offers the performance and comfort of cutting edge athletic footwear. But if it turns out that there’s no market for shoes that look like boats, that product would fail—regardless of its beauty or functionality. In short, it doesn’t matter if the answer is right if the question you set out to answer is wrong. It’s the job of the product manager to ensure that the product team is working to answer the right question(s).

I think Ernest really nails it. Asking the right question is as important as coming up with the right solution. Out of respect for how hard it is to ship a great solution to market, I don’t want to say it’s more important, but it is really important.