If you’re at all like me, unproductive meetings are likely the bane of your existence. We’ve all been there: the conversation meanders, 50 minutes disappears from your life, and you’re no closer to your goal than when you started. At IDEO we dislike these kinds of meetings too. So we found a simple but elegant solution, captured by my colleague Dennis Boyle, in a saying I call “Boyle’s Law”:

“Never attend a meeting without a prototype”*

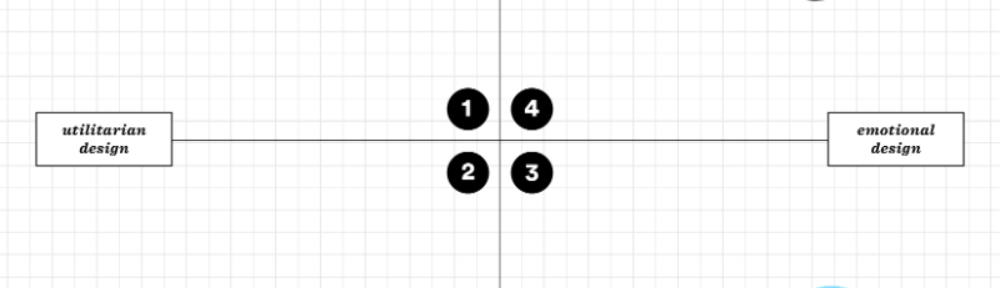

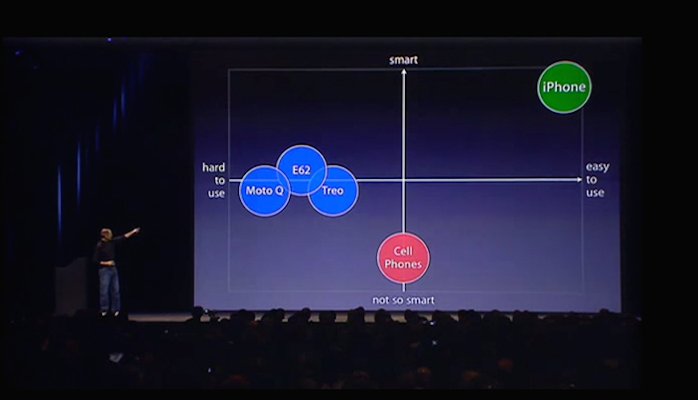

This law creates better meetings in three big ways. But before we get there, it’s worth asking: what is a prototype, exactly? We’re in the business of design and innovation at IDEO, and we use the word quite liberally. When I was a practicing engineer, a prototype was something that made a sound when you dropped it, but these days I define it as a single question made tangible. It’s lines of software code, a business model spreadsheet, or a few people acting out a service experience.

If it takes what’s in your head and creates something tangible that others can react to—if it helps probe the unknown—it’s a prototype. And I believe that you can prototype new ideas in your workplace, no matter its focus.

Expect three things to happen when you start bringing prototypes to your meetings:

First, a lot of your meetings will evaporate. Those that shouldn’t happen in the first place, the ones where nothing gets done, won’t. If you can’t bring a prototype of your latest thinking, there’s a simple solution: don’t have the meeting. Instead, focus your precious time and energy on making actual progress.

Second, the meetings you do have will be awesome. With something concrete in the room, discussions will be more productive and actionable, and the level of shared understanding and alignment will go through the roof. And instead of grappling with all the fears, doubts, uncertainties, worries, hidden agendas, and politics that bedevil any organization, you can focus all of that negativity on the prototype—it has no feelings or career prospects, and it just doesn’t care! As you critique, elephants in the room—the real problems at hand—will magically surface, ready to be addressed.

Finally, bring more prototypes to meetings, and you’ll boost levels of performance and engagement across your organization. Professor Teresa Amabile of Harvard Business School has shown that a sense of progress is the driving factor behind high levels of reported happiness and work satisfaction in the workplace. Not fancy coffee or bean bag chairs, just employees knowing that they’re making progress toward their goals. A prototype is an embodiment of all the work you’ve done, and it’s an easy, positive way to signal and celebrate forward motion. Meetings suddenly shift from being deep wells of dread to wellsprings of happiness.

But you say, I like meeting all the time! Well then, here’s another simple solution: create more prototypes! They’re the gift that keeps on giving.

So, what prototype are you going to bring to your next meeting?

* design engineering humor