I hadn’t read a book in a single sitting since a long night in March, 1995, when I read Ondaatje’s The English Patient after taking The Chunnel from Paris to London. Just as a movie is more satisfying when consumed as a flow experience, a good book begs to be consumed in whole. Last week I had the rare pleasure of spending an evening having just this type of superlative book experience in the form of John Maeda’s The Laws of Simplicity. I devoured it. I’m already using its lessons in my daily work. And I look forward to reading it again soon — I think it’s the most important book I’ve read since Don Norman’s Emotional Design.

In this tidy book of just 100 pages, John Maeda walks us through 10 Laws of Simplicity. This being 2006, I don’t need to list them because you’re better off reading them on his Laws of Simplicty blog (be sure to click on the laws listed down the right column of the page). I’m particularly enamored of Law 10: The One, which is stated as such:

Simplicity is about subtracting the obvious, and adding the meaningful

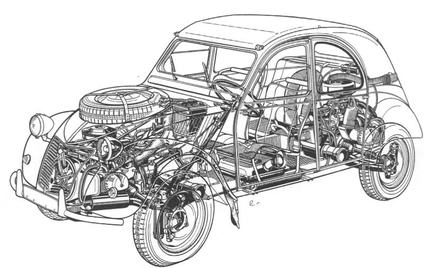

Adding the meaningful. Think about that. When we strip out the obvious, we edge closer to root nuggets where real value resides. Meaning is what we seek, what leads to happiness. The obvious is banal because it is obvious; there’s no challenge or satisfaction in its consumption. And I believe this state of simplicity is what gives us "universal" offerings and brands such as the iPod, the Citroen 2CV, the Golden Gate Bridge, Muji — each embody Roger Ebert’s sage observation that "The more specific a film is, the more universal, because the more it understands individual characters, the more it applies to everyone." Unique designs appeal to so many of us exactly because they don’t try to appeal to all of us. We want the elegant simplicity of rich meaning.