In music there's a big difference between Mick Jagger and Maria Callas. If you're a pilot, hopping a bush plane around Alaska requires a different skill set you need to grease a 747 on the runway in Hong Kong.

And so it is with innovation: it comes in many flavors, and the ability to discern those flavors and proceed accordingly is a foundational of skill of individuals and organizations who are able to achieve innovation outcomes on a routine basis.

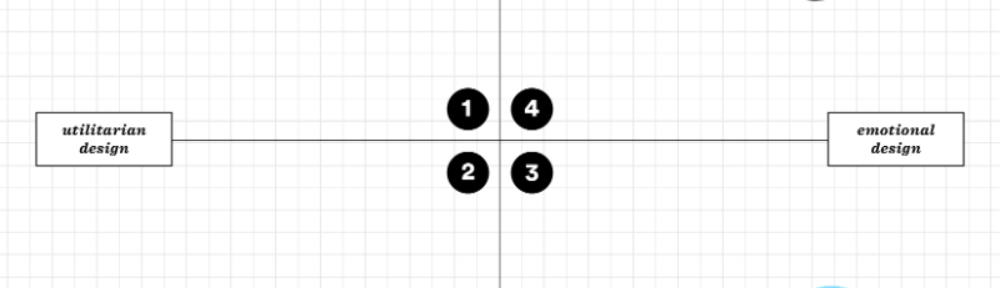

This is most easily explained using a 2 x 2 matrix. I promise this is the only 2 x 2 I will be using in the course of this ongoing discussion of innovation principles:

No matter where you want to go tomorrow, today you and your organization sit at the lower left vertex of this 2 x 2. So, looking up the vertical axis, you start with the offerings that you currently deliver to the market, and then range up to things that are new to you. Then, looking out across the horizontal axis, you start with the people you know, and out at the end of the axis you have people (or users) you don't know at all. The four quadrants of the 2 x 2 then fall out as follows:

- lower left: existing offerings for existing people

- upper left: new offerings for existing people

- lower right: existing offerings for new users

- upper right: new offerings for new users

Three different flavors of innovation are defined by these quadrants:

- Incremental Innovation: you seek to deliver improvements to offerings you already sell to people who you understand fairly well. Your capabilities as an organization are designed to deliver these offerings to these people.

- Evolutionary Innovation: one aspect of your offering (either unfamiliar people or an unfamiliar offering space) is changing as you seek to bring new something to market, forcing you to evolve away from what you know. Your mainstream organization will be only partially equipped to successfully innovate here.

- Revolutionary Innovation: the proverbial blank sheet of paper. Everything is new, as you don't have a history with the offerings, nor do you understand the people here. Your mainstream organization not only is not equipped to innovate successfully here, it won't even see the value in innovating here.

For each type of innovation to work, different organizational structures, metrics for success, development processes, individual skillsets, financial structures, even seating arrangments and reward structures must be put in to place. Just as you wouldn't take a 747 to reach an Alaskan fishing village, so too you wouldn't try to go after a revolutionary innovation outcome using a team and structure built for incremental outcomes. But it happens all the time, ergo the need to develop a taste for these flavors. Innovation efforts are more likely to fail due to flawed architectural decisions made during their genesis than because of a lack of effort or luck on the part of the participants who put that architecture in to action.

There is no value judgment being applied across these three flavors of innovation. Though "revolutionary" innovation is the flavor which captures the imagination of the public, incremental innovation is what keeps the lights on and your brands relevant in the short term. But revolutionary innovations are what lead to breakthroughs that build value for the future. In reality, a healthy organization must maintain a portfolio of innovation initiatives across this landscape if it wants to stay healthy for the long haul.

I am the last person to claim that this is a definitive model for understanding the landscape of innovation. But in my experience it is simple enough to be used in practice, yet not so simplistic that it yields erroneous outcomes. For more depth, please reference the following paper authored by Ryan Jacoby and yours truly.

This is the seventh of 21 principles. Please give me your feedback, thoughts, and ideas.