Schlepped down to the local Apple store the other day and picked up a minty new iPod. Needless to say, I’m a very happy new iPod owner. But this post isn’t another ode to Ive’s tiny white brick – I’ve already written that one. Instead, let’s talk about the bag it came in.

The bag. Dangling from my hand, it made me feel so good walking down the street after issuing grievous wounds to my Visa. The relatively dense iPod package felt secure within the plastic bag material, whose silver finish positively glinted in the late summer sun, and the two carrying cords were positively intriguing: do I sling it from my hand or shoulder like a sack, or do I go for the metrosexual thing and wear it as a mini backpack.? I went the sack route.

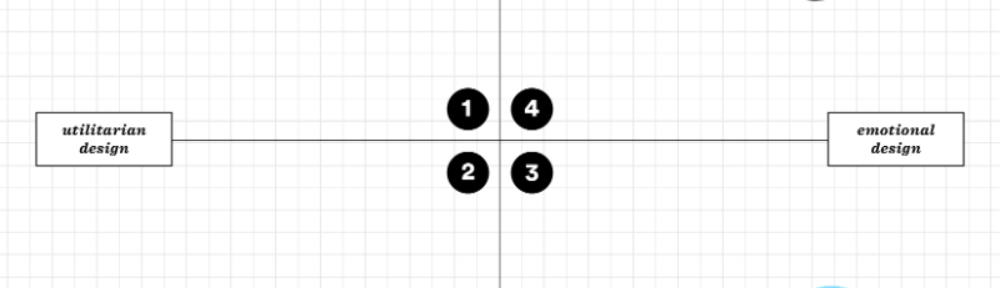

So it’s a beautiful, wonderful thing of a bag. Again, Norman’s tripartite model of cognition helps analyze what’s going on here at a more intellectual level:

Visceral (feel): silver, smooth, shiny, whole and integral – all pure Apple aesthetics.

Behavioral (function): a bag’s bag, with a wide, closable mouth, strong material, stout metal eyelets to increase load capacity, resilient plastic material, convenient carrying cord which allows multiple bearing modes.

Reflective (meaning): I rarely feel good about carrying a branded shopping bag, but I felt proud to have this thing – “Hey, he just bought something at the Apple store – cool!”

Not surprising that Apple would do a bag so well. From the standpoint of building and enhancing the brand, this bag is worth ten times any incremental cost over a more mundane solution. It’s about a seamless brand experience.