Professor Matt Kahn passed away a few weeks ago. He was my teacher, and had a big impact on my life.

I met him during the 1990-1991 school year, which was a pivotal one for me. It’s the year where I found my North Star and got serious about pursuing my formal training as a designer. I was fortunate to spend that summer studying at Stanford’s program at Oxford. Most of my evenings were spent in jazz clubs in London, and on weekends I discovered the twin joys of live Formula 1 television broadcasts hosted by Murray Walker and the joy of living in a place where so much of the built environment had been designed and engineered with a high degree of consideration. What an amazing chance to live a few months of my life as a flaneur. Both were good food for thought.

Up to this point in college I had been unable to resolve a fundamental tension between my love of the humanities and all the writing and reading and the critical thinking which goes along with that domain, and my abiding love of all things mechanical (especially the loud and fast ones). In a nutshell, I couldn’t figure out whether I wanted to be more like Stephen Barley or Gordon Murray. And then one Sunday morning over an informal breakfast, a very wise fellow student suggested that I just do both and get on with it.

And so I did. I came back to campus that Fall and formally began the mechanical engineering design curriculum, and in the spirit of doing both found a way to also study for a humanities degree via Stanford’s amazing STS program. During that year I took an array of design classes whose lessons I still use each and every day, delivered by a truly inspiring group of teachers, including David Beach, Brendan Boyle, David Kelley, and Matt Kahn.

Matt Kahn taught his foundational Art 60 class with a classic Beaux-Arts approach, meaning that we walked in each day and placed our completed, unsigned assignments on the board (or on a table) before class, and then sat and listened the give and take of Professor Kahn’s critique as he made his way through all the content around the room. The title of Art 60 is “Design I: Fundamental Visual Language”, and in it you had to complete a certain number of projects of your choosing from a list given out at the start of the quarter. Professor Kahn, as David Kelley notes, had a truly singular talent for critique, and so these sessions were often some balance of intellectual enlightenment and personal (but temporary) devastation.

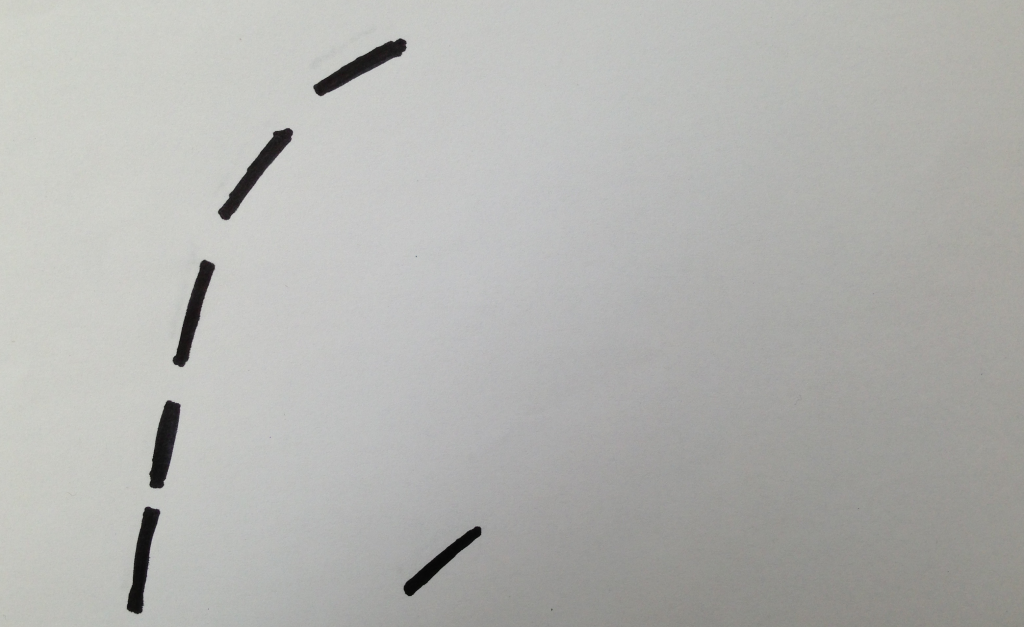

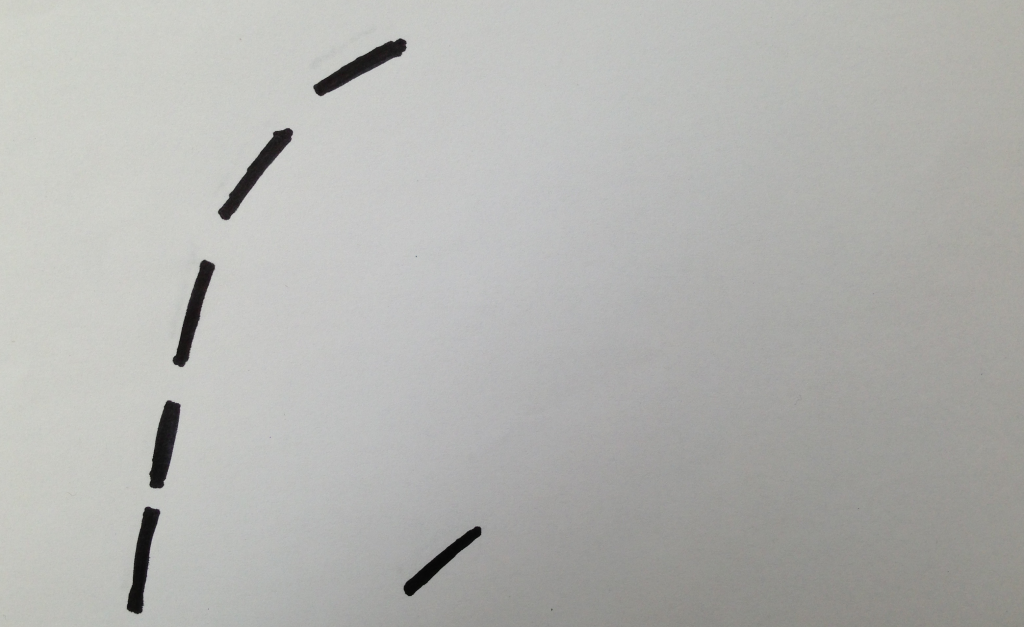

I really struggled for the first month or so of class. I wasn’t getting it, not at all. Ever persistent, I kept plugging away. One day I brought in my approach to an assignment which I believe asked you to take a small number of geometric objects and arrange them in a way that conveyed a feeling or emotion. Using construction paper, I pasted up a composition, brought it to class, hung it on the wall, and then took a seat on one of the stools scattered around the studio. My intention was to show what being freaked out by something feels like, and it looked like this:

Professor Kahn walked in, and looked around the room, and zeroed in on my piece of work.

Gulp.

“Who did this?” he asked, with an arch of his eyebrows. I raised my hand up to about chest level and gave a half-hearted wave.

Calmly stepping toward me, he gave me that squint of his, cocked his head a bit to one side, smiled a wry smile, and then slowly and in a strong voice said,”Who. Are. You. Afraid. Of?”

Here was his incredible ability to critique the work of others and express it all concisely and with great elegance. In a millisecond he nailed exactly what I was feeling and thinking when I created that piece of artwork. Basically, I was scared of being in Art 60. I was frightened by the prospect of screwing up in front of Matt Kahn. In that moment, with Professor Kahn staring at me, my internal voice was urging me to respond with the truth: “Answer him with a big ‘YOU! It’s YOU I’m scared of, Professor Kahn!'” But before I could stop myself, I blurted out a fuzzy statement along the lines of “Oh no no no no… what I was trying to communicate here was the sense of something being herded or corraled, you know…”

He smiled again. Paused. And then quietly said that it was more powerful the way he had described it, and how it worked well when seen from that perspective. He knew. And then he squinted again at me, gave me another dose of that inscrutable smile of his, and moved on to discussing the next student project. I got it—I had done good, but I could do better if I could learn to embrace it all with abandon.

Great teachers have a way of seeing your potential and finding a way to get you there. They give you challenges and allow you to fail along the way—and let you know it—but never so much that you give up on your dreams. Matt Kahn was one of the great teachers in my life. He built confidence in my own creative process as a designer, and for that I will be forever grateful.

Thank you, Professor Kahn.