To paraphrase Jerry Seinfeld, comedy writing and car design are two things you don’t see people doing in public. So here’s a video peek at Seinfeld’s private creative process—and that of Michael Mauer and Mitja Borkert, both design leaders at Porsche. When it comes to revving up your own creative process, they’re inspiring studies.

How do these three creative masters do what they do? Let’s watch and see what we can learn:

Seinfeld, Mauer, and Borkert are all extremely thoughtful about their craft and dedicated to constantly raising the bar for what “good” looks like. These videos are master classes in creativity, with five important takeaways:

Insist on Great Fundamentals. All three know the power of getting the creative rocket pointed in the right direction. For car designs, Borkert declares “…the proportions are the crucial beginning of any project.” The same holds true for jokes, where Seinfeld says “I like the first line to be funny right away.” They don’t spend energy making a lousy shape attractive, or a bad joke funny. It’s about having the right architecture from the start. Seinfeld even talks about his comedy writing in structural terms, saying “…I’m looking for the connective tissue that gives me that really tight, smooth link, like a jigsaw puzzle.” The creative process for both great cars and great jokes starts with great fundamentals.

Obsess Over Details. All three focus on the kinds of details—from minute surface transitions on a windshield to nuances of syllables in a string of words—that none of us civilians ever notice. Except that we do, because when it comes to great things, it’s the overall experience we remember, and that experience is shaped by myriad details whose sum is greater than the parts. Details such as the fun index of a string of words like “chimps in the dirt playing with sticks”. Details such as the depth of an air outlet. At the seven minute mark you can hear Mauer questioning a surface transition on the back bumper of the Panamera. As a layperson, I couldn’t see anything amiss, but you know it was a big deal for them. Details matter.

Pack the Right Tools. For creativity to effect change in the world, it requires expression. Seinfeld’s tools are yellow legal pads and blue Bic pens. The Porsche equipment used by Mauer and Borkert costs quite a bit more, but they have it all at hand, too. Having the right tools nearby deftly eliminates the procrastinator’s excuse of “I could be creative if only I had the right pen.” Pack your tools, get going, and create!

Lather. Rinse. Repeat. Creativity is hard work. Edison’s observations about 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration are true. It can be tempting to take the path of least resistance. But when faced with thorny challenges, gritty optimism is the wellspring for creativity and magic solutions. Interestingly, both Seinfeld and Mauer found it a challenge to resolve their respective tale and tail. For Seinfeld, it required hard work to uncover the breakthrough Pop Tarts line, “…they can’t go stale because they were never fresh”. For Mauer, the right shape for the Porsche station wagon was terra incognita: “…the rear of it is certainly the greatest challenge—we never had that kind of car at Porsche before.” Designers made piles of sketches, stared at clay models, and iterated often to come up with that beautiful 3D Porsche signature effect. Whether it’s a car or a joke, lathering, rinsing, and repeating—over and over—is what transforms good into great.

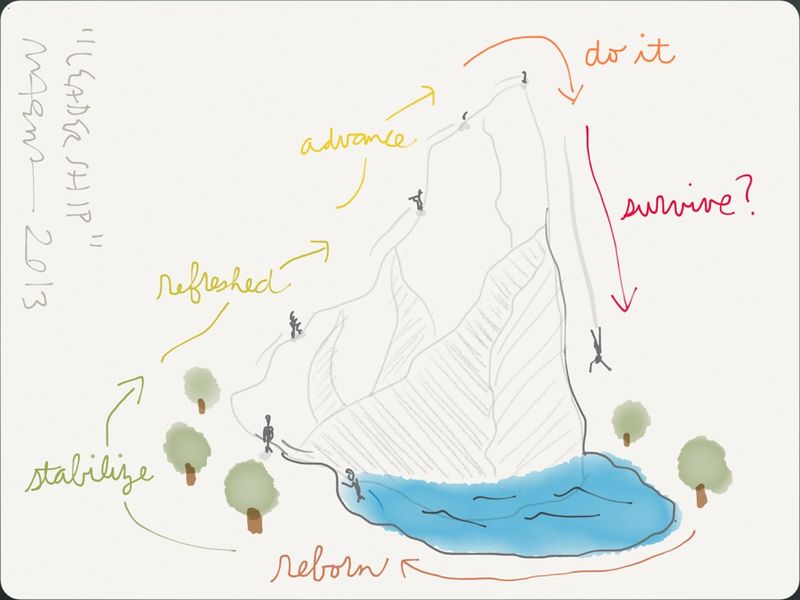

Master Your Creative Domain (But Then Forget About It). Notice how fluid the creative process feels for Seinfeld and the Porsche designers. A creative process isn’t something you learn in a day and use forever, and it isn’t a set of simple steps you read out of a manual. It takes years to develop, and the more you use it, the more your confidence grows. Drawing, surfing, playing the piano—it’s true for all creative endeavors. At some point you move beyond rote process so that it all becomes your natural way of being, what you were put on earth to do. Then you can create like the masters Seinfeld and Mauer and Borkert, with great confidence, joy, energy, and total engagement in the task at hand. First you master the art, then your own process, then you forget all that and just do it.

There’s a universal creative process we all share—but as many permutations of it exist as there are people on the planet. The point is to be conscious of your own process, and to always be evolving it. Now, I’ll never write a joke like Seinfeld or profile a headlamp like Mauer, but I can learn from the specifics of their creative approach in order to improve my own. In the details of another person’s creative process are the universals we can all learn from.

(a version of this post also appeared on my LinkedIn Influencers page)